Finishing off our evening shopping trip and our British attempts at ‘haggling’, we nestled down in one of Belgins’ huge cushion chairs – a traditional Turkish restaurant with the kind of decor which would fit Alibaba’s cave of treasures. Large groups sat round low tables with plump cushions and over worn carpets, passing round the traditional Hookah pipe. Compelled to at least to try, we order our waterpipe and slowly choked are way on steam (smoking does not come naturally to me!), plenty of the relaxed pros tried not to tut too loudly.

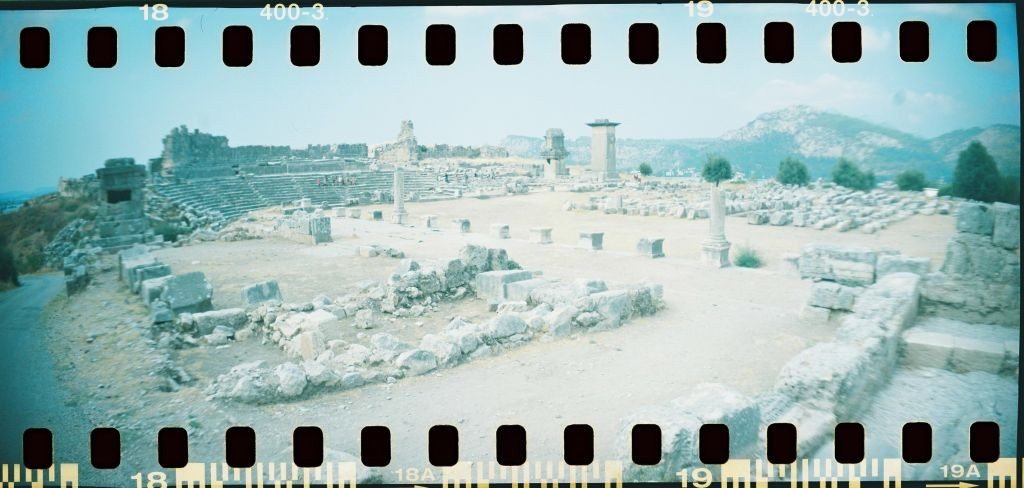

In the footsteps of Sir Charles Fellows, we decided to venture back towards Fethiye in search of the ancient ruins of Xanthos and Letoon. The ruins of Xanthos cover a wide hill with a steep drop overlooking one of the few fertile valleys in the region, fed by snow water melt from the Ak Dag mountain in the background. Today’s poly-tunnels and modern agricultural landscape lie as far as the eye can see growing tomatoes. Xanthos was the principal city of Lycia (but then every town claims to be that), but at Xanthos the scale and might of the ruins certainly reaffirms the town’s position and represents the strong-willed character of Xanthians.

In the footsteps of Sir Charles Fellows, we decided to venture back towards Fethiye in search of the ancient ruins of Xanthos and Letoon. The ruins of Xanthos cover a wide hill with a steep drop overlooking one of the few fertile valleys in the region, fed by snow water melt from the Ak Dag mountain in the background. Today’s poly-tunnels and modern agricultural landscape lie as far as the eye can see growing tomatoes. Xanthos was the principal city of Lycia (but then every town claims to be that), but at Xanthos the scale and might of the ruins certainly reaffirms the town’s position and represents the strong-willed character of Xanthians.

In 450BC, Herodutus describes how the inhabitants set the city alight and committed mass suicide during a siege by the Persians, only to perform the same ritual again when invaded by the Roman Brutus in 42BC. The city’s prominence was restored under Alexander the Great and the Romans, but as the mouth of the River Xanthos silted up, the city sank into decline and further oblivion after the Arab invasions.

Sir Charles Fellows, a gentlemanly antiquarian, first stumbled upon the ruins of Xanthos in 1838. As Sarah Searright, in her paper ‘The British Museum and the Xanthos Marbles’, describes him ‘antiquarians resemble missionaries in their zeal to rescue lost antiquities, or souls, from the heathen.’ Sir Charles was alarmed, shocked and appalled at how local inhabitants (according to Fellows journal) had stripped the ruins for building materials despite their unique Lycian character. On his return to Great Britain, he campaigned for the British Museum to send him back to rescue the ‘Xanthos Marbles’. Today, under these different perspectives of nationalism, the author, Hakki Tor, of my Turkish guide book, ‘Lycia – Shiny Territory in Anatolia’ has this to say on the matter:

‘Xanthos, the noble city, famed for rebelling against tyrannical invaders and plunderers over centuries, was rendered helpless in the face of historical looting of Sir Charles Fellows in 1838 on behalf of the British Museum. Notwithstanding hundred of articles belonging to such a splendid civilisation brutally removed from the site and shipped, miles away from where they belong to England, the remaining pieces are still the most beautifully representative of the Lycian region’

Suffice to say that Sir Charles Fellows, whose name crops up like a bad smell all the way along the Lycian coast, has a lot to answer for. The most conspicuous ruins such as the Roman ampitheatre and beside it, the two tombs – the Harpy and great pillar tomb in the typical style of wooden Lycian house, remain. However the original reliefs of the so-called Harpy Tomb, named after the winged women lifting soul to the afterlife depict in the reliefs, are now exhibited in the British Museum.

It took Fellows sometime to finally remove the marbles from Xanthos, keeping up pressure on the British Ambassador, Lord Ponsonby, to arrange the necessary license or firman with the current sheikh and eventually, Fellows moved 80 tonnes of marble fragments and was knighted for his efforts.

Searright writes after the reassembly of the Nereid Monument, also from Xanthos, depicting ‘life size girls who stand in transparent draperies, posed for flight.’

‘They are, possibly, the best justification for the marbles staying where they are. Though all have been deprived of their heads by marauders, the power of the [Nereid] sculpture makes them a vivid testimonial to the culture of this corner of the classical world, a culture of which millions today who visit the British Museum would otherwise know little.’